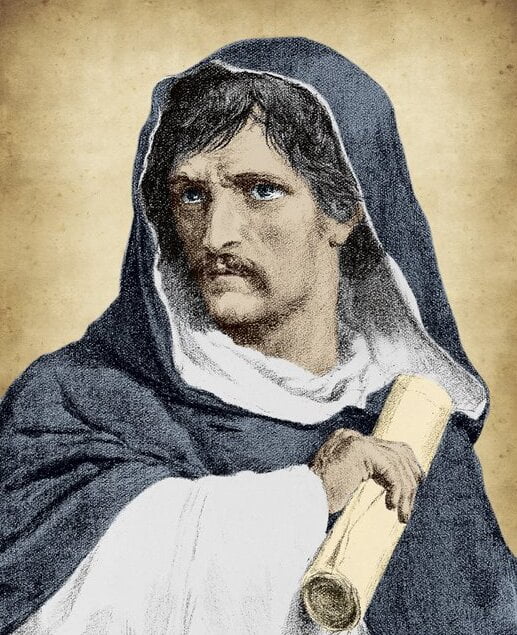

Giordano Bruno, an Italian philosopher, mathematician, and cosmologist, was indeed burned at the stake on February 17, 1600, in Rome. His execution remains one of the most controversial and significant episodes in the history of the relationship between science, religion, and the struggle for intellectual freedom during the Renaissance era.

Born Filippo Bruno in 1548 in Nola, Italy, he later took the name Giordano when he joined the Dominican Order at the age of 17. From a young age, Bruno displayed exceptional intellectual abilities and an insatiable thirst for knowledge. As he delved into various fields of study, his ideas began to challenge prevailing religious and philosophical norms, setting the stage for the conflicts that would eventually lead to his tragic end.

Giordano Bruno journey as a thinker was deeply influenced by the Renaissance’s spirit of inquiry and the rediscovery of classical Greek and Roman texts. He embraced the Copernican heliocentric model of the universe, which posited that the Earth revolved around the Sun, in contrast to the widely accepted geocentric model espoused by the Catholic Church. His cosmological views were revolutionary, and he was an early proponent of the idea that the universe was infinite, populated by countless other worlds, and that there was no center.

In addition to his cosmological theories, Bruno was an advocate for the unity of all knowledge. He believed that philosophical and scientific truths were interconnected and that religious dogma should not constrain human understanding. This stance brought him into conflict with the Catholic Church, which held considerable authority over matters of faith and was not tolerant of ideas that challenged its teachings.

In 1576, Bruno fled Italy after facing accusations of heresy due to his unconventional beliefs and non-conformist lifestyle. He traveled extensively throughout Europe, engaging in debates, teaching, and writing prolifically. However, his wanderings also exposed him to the Inquisition, which was tasked with rooting out heresy and ensuring doctrinal purity within the Church.

In 1592, Bruno settled in Venice and published his most significant work, “De Immenso et Innumerabilibus” (On the Infinite and the Innumerable). This treatise presented his cosmological ideas and further questioned traditional religious teachings. Bruno’s combative style and lack of diplomatic finesse made him many enemies within the academic and religious establishment.

In 1593, he was arrested by the Roman Inquisition after the Protestant theologian Johannes Kepler reported him as a heretic. During his eight-year imprisonment and subsequent trial, Bruno staunchly defended his ideas, refusing to recant his beliefs, despite the severe torture he endured. The Inquisition charged him with heresy, blasphemy, and other religious offenses, and despite some leniency initially shown by the Inquisitors, the pressure to abandon his convictions became unbearable.

Ultimately, Bruno’s fate was sealed when Pope Clement VIII personally approved his sentence. On the day of his execution, he was brought to Campo de’ Fiori, a square in Rome, and burned at the stake. The authorities hoped that by making Bruno’s death a public spectacle, they would deter others from questioning the Church’s teachings.

However, Bruno’s death did not silence his ideas; it instead turned him into a martyr for intellectual freedom and a symbol of resistance against oppressive religious authority. As the centuries passed, his writings gained appreciation for their contributions to the development of modern scientific thought.

In the modern era, Giordano Bruno is celebrated as an early advocate of scientific inquiry and the pursuit of knowledge without fear of persecution. His legacy serves as a reminder of the importance of protecting freedom of thought and expression, and his tragic fate stands as a stark cautionary tale against the suppression of ideas and the abuse of power in the pursuit of truth.